The Dilemma of a Marine Biologist

Lynn Jula Kessler Photos

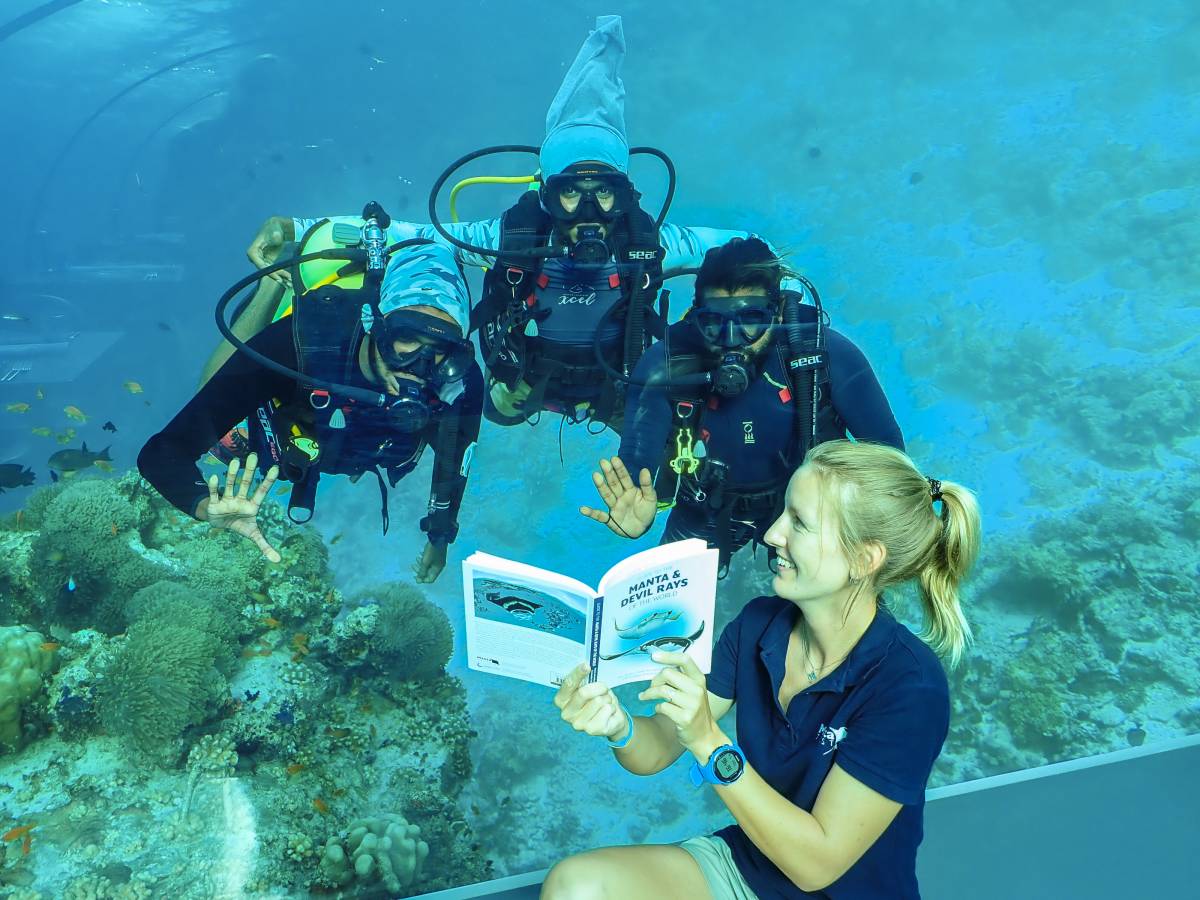

Irene Millar in conversation with Lynn Jula Kessler, Marine Biologist, Outrigger Maldives Maafushivaru Resort on International Whale Shark Day, 30th August 2022.

(September 11, 2022) Picturing the Maldives in my mind’s eye conjures up white powdery beaches, crystal clear blue waters and a never-ending azure sky. Calmness, peace and tranquility in abundance. That picture was quickly dispersed by a frank, and at times painful, conversation with Lynn Kessler, Marine Biologist at Outrigger Maldives Maafushivaru Resort.

Lynn dreamed of becoming a marine biologist from a young age. Not being gifted with the educational qualifications in maths and science normally required, Lynn followed an unconventional route combining a degree in Cultural Studies, a Masters degree in Environment and Resource Management, with Scuba Diving Instructor certification to realise her childhood dream. Following this path has fully equipped Lynn with the tools to conserve what she loves. Outrigger guests have the opportunity to learn about marine conservation from Lynn during twice-weekly evening educational talks on the challenges facing whale sharks, turtles, manta rays and coral reefs.

As an island nation, the Maldives government is acutely aware of the dangers posed by climate change and the benefits of marine protection. All sharks and rays are protected by law, and are not allowed to be fished. Lynn explained that protection for reef manta rays is easier to monitor and enforce as they don’t migrate outside the Maldives. Whilst the waters frequented by whale sharks around the Maldives are protected, they, and oceanic manta rays, travel huge distances, crossing borders and making conservation efforts a lot more challenging.

Lynn works closely with the international charity Manta Trust, and a local charity Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme (MWSRP). Data collected by Lynn during guest excursions, detailing sightings of rays and sharks, is reported to the relevant charities.

The charities collate and analyse the data provided by marine biologists, divers and tour operators, and share their findings with the Maldives authorities. Globally, manta rays are faced with a number of threats, and giant manta rays are listed as ‘endangered’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The Manta Trust has, with the support of government legislation, seen the population of manta rays stabilise in the Maldives. The whale shark population in the Maldives has not been so fortunate.

Whilst whale sharks encounter many risks, a significant contributing factor to the current decline in the whale shark population around the Maldives is one that is entirely preventable – unsustainable tourism.

The pressure on tour operators and boat captains to deliver whale shark sightings to tourists, along with the desperation to earn income after an enforced hiatus during Covid 19, combine to drive unsustainable tourism. Tour operators and boat captains worry that tourists may leave bad reviews on social media if they don’t encounter a whale shark during their excursion. Whale sharks don’t appear by appointment, and there is a 50/50 chance of not seeing one during an excursion.

The South Ari area of the Maldives is an important focal point for whale sharks, and they visit here on a regular basis. It’s an ideal location for them as it provides access to deep ocean, which is where marine biologists assume they feed, and the edge of the atoll to cruise along to warm up.

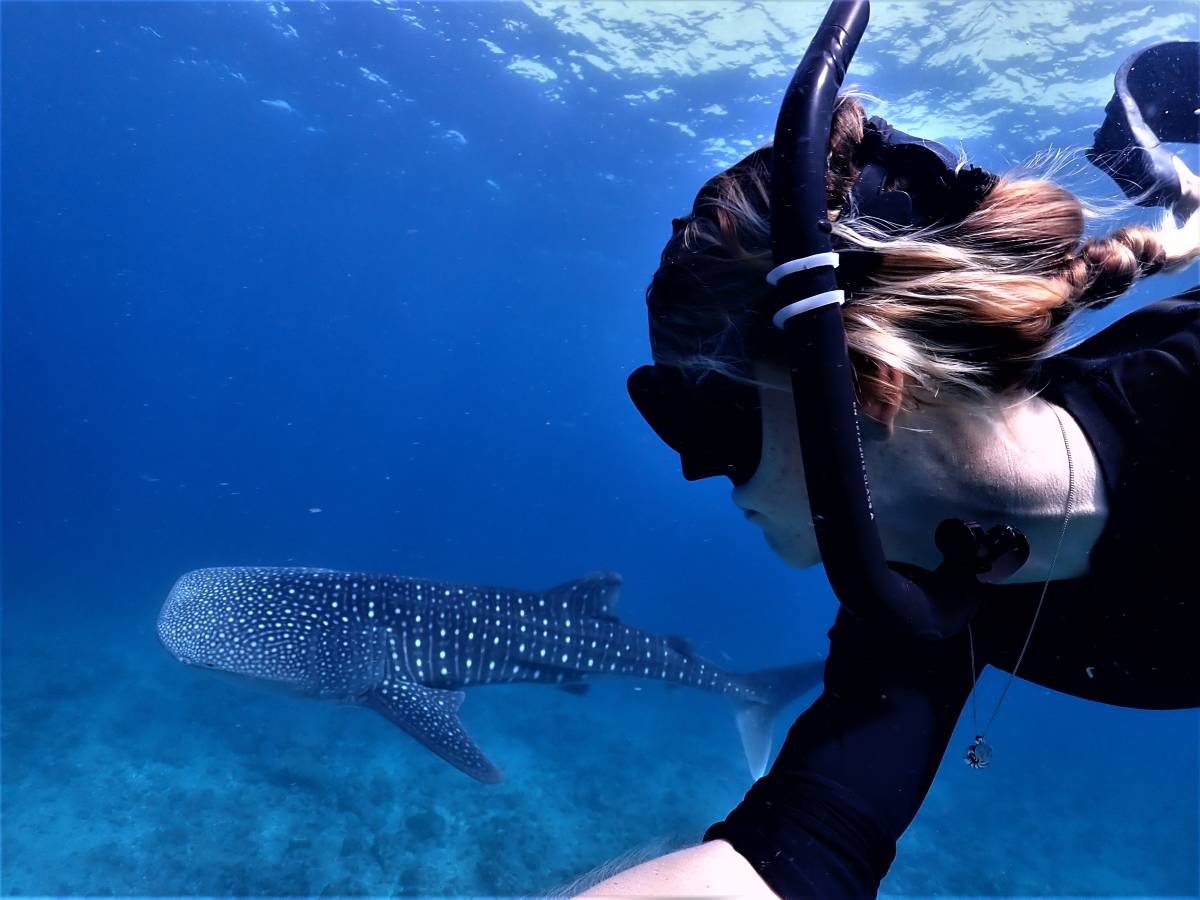

The South Ari acts as a secondary nursery for whale sharks where juveniles between five and eight meters can be sighted. Fully grown, a whale shark can reach 17 meters in length. Despite their enormity, whale sharks of any size, are not aggressive, even if threatened. However, if you move too close to one, you may experience a slap from its powerful tail as it dives to evade you.

Whale sharks are solitary animals and don’t tend to spend time interacting with each other. An abundance of plankton to feed on in a concentrated area may provide a rare opportunity to see more than one.

So, what are you likely to experience on an excursion to see a whale shark? Lynn revealed that the reality is very different from a common guest misconception of this being an idyllic one-on-one moment with a whale shark in a calm and peaceful setting in the middle of the ocean.

Each tour boat is in contact with all the other tour boats, and any sighting of a whale shark is broadcast to each one. This is the equivalent of the horn at the start of a regatta, with boats ignoring the speed limits set for the South Ari Marine Protected Area, in a race across the water to the same location in an attempt to be the first to disgorge their passengers into the water. If guests aren’t on the first few boats arriving at the location, the chances of later arrivals seeing a whale shark are low.

Undisturbed, whale sharks stay at the surface of the water for 20 to 30 minutes, enough time for everyone in the vicinity to see it and have an enjoyable experience. A disturbed shark is likely to dive in less than five minutes to escape the commotion on the surface. Whale sharks are non-tactile animals who become stressed by people swimming too close, or even worse, touching them.

Tourism is creating chaotic encounters, with up to 80 people at a time all following the whale shark in an attempt to capture a ‘selfie’. Many social media devotees aren’t respectful of space, and they want to be as close as possible to the whale shark. People turn what should be a peaceful and wonderous encounter into a frenzy in their pursuit of the immediate gratification of an ‘insta’ moment.

Human behaviour can cause unintended stress and disturbance, and unfortunately, unsustainable tourism is now changing the behaviour of the whale sharks leading to them becoming more evasive of the tour boats. The whale sharks have become a victim of their own success and they provide us with a very poignant example at what unsustainable tourism looks like. It would be ironic if unsustainable tourism pushes the whale sharks to find another location where they can cool and warm in peace. Without the whale sharks there would be fewer tourist excursions, resulting in less income for the boat captains and tour operators. A loss for the whale sharks, guests and everyone involved in the excursions.

The Environmental Protection Agency introduced guidelines, based on data research and shared knowledge from MWSRP, for whale shark tourist encounters in 2009. The guidelines are still in place today, however lack of enforcement of regulation results in many boats not following them. MWSRP continues to build data in the hope that enforcement of regulations will be introduced to support sustainable tourism for whale shark excursions.

In the meantime. if you are considering joining an excursion to experience whale sharks, choose a tour operator who follows the Maldivian Whale Shark Tourist Encounter Guidelines and the Code of Conduct. Outrigger Maldives fully adheres to both the guidelines and code of conduct on all guest whale shark spotting trips. This is the best way to share ocean space and minimise stress and disturbance to the whale shark. Key aspects to the Code include;

- respecting the whale shark’s space by maintaining a minimum distance of three meters between you and the whale shark at all times, and not blocking its direction of travel

- minimising noise, this includes entering the water and whilst you are in the water. No shouting or splashing around.

To enjoy an encounter with a whale shark you must be comfortable in deep water, and with a snorkel. If you are an inexperienced swimmer, then don’t throw yourself in at the deep end with the largest fish in the world, panic is likely to ensue!

Lynn believes that introducing people to conservation is a vital component in creating a connection and emotional attachment to an eco-system or species. This however creates a dilemma, ‘I am part of the problem, as I am taking tourists out and disturbing the whale sharks.’ Equally, the excursions help guests better understand the marine environment, which hopefully encourages them to support conservation efforts.

During excursions guests may see a whale shark which has sustained injuries from boat propellers. Whale sharks are a slow-moving animal and don’t have time to avoid collisions from fast moving boats hurtling towards them. This often leads to guests realising the reason why speed restrictions on the water are an important aspect in the safety of marine life. It supports Lynn’s belief that we can only reach sustainable whale shark tourism by the inclusion of guests experiencing the realm of the whale sharks, and then becoming advocates of sustainable practices.

Operating sustainable excursions requires everyone to play their part in following the rules to protect the whale sharks. Tourists have a key role to play in this by choosing a tour operator who adheres to the guidelines, and a professional guide, like Lynn, who briefs guests on the Code of Conduct. The guide’s priority is to make the encounter positive for the whale shark, which will in turn make it positive for guests. Following the guide’s instructions is the most effective way to enjoy the opportunity to experience a memorable encounter with a whale shark.

My thanks to Lynn, for sharing this story, and for the work she does daily to protect marine life for travellers to enjoy both now and in the future. Her passion and tenacity to conserve what she loves reverberated throughout our conversation.

"As long as I am going out there, I can make sure that boat captains and guests adhere to the standards to protect the whale sharks."

More information on the issues and solutions outlined in this article is available in the following links:

Outrigger Maldives Maafushivaru Resort:https://www.outrigger.com/hotels-resorts/maldives/outrigger-maldives-maafushivaru-resort#section-experiences

Manta Trust: https://www.mantatrust.org/

Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme: https://maldiveswhalesharkresearch.org/

Maldivian Whale Shark Tourist Encounter Guidelines and Code of Conduct: https://maldiveswhalesharkresearch.org/research/sustainable-tourism/