Navigating Human Elephant Conflict

Irene Millar in Conversation with Ravi Corea, President of the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society

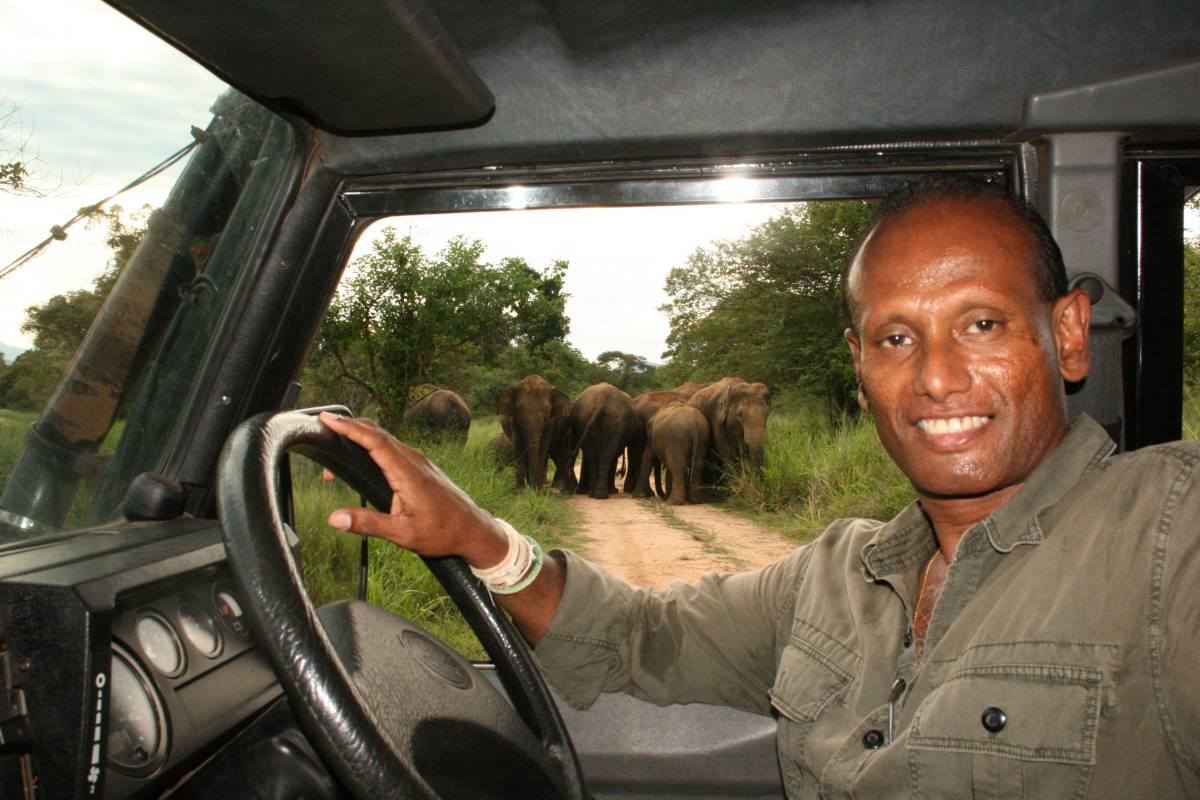

(Singapore April 4, 2022) Ravi Corea’s (pictured below)love for conservation started at an early age. As a boy, he and his friends, would escape their suburban environment to play in the surrounding marshes. These marshes became their open-air classroom where they learned about nature. He describes it as ‘a vast expanse of infinite landscape.’ The marshes, home to an eco-system, and a place that inspired younger generations to appreciate nature, were viewed by others as wasteland. In less than 10 years, the marshes were destroyed by development. ‘The footsteps of our childhood in the marshes were erased with concrete and steel.’ This is a story that resonates with my own childhood. The vacant field where we played during the day, and where at night we would gaze in wonder at the stars as my Dad guided us through the constellations, also fell prey to bulldozers and construction.

Sri Lanka, where Ravi grew up, is a biodiversity hotspot. Conversely it also has a large and growing human population with a large percentage of the population generating their income and livelihoods from agriculture. Agriculture requires land, but requisitioning land for agriculture comes at the expense of biodiversity.

Earning a living in Sri Lanka from small scale agriculture is hard, with farmers facing many challenges. Changing weather patterns, too much, or too little rain, together with traditional practices rather than modern farming technologies all impact on what can be harvested. Farmers are understandably angry and frustrated when elephants destroy their crops. On the other hand, elephants are looking for food in what used to be forest, their natural grazing habitat. Clearing these forest habitats and planting crops that are highly attractive to elephants is a recipe for disaster. This growing competition for land, and food, creates increasing conflict between humans and nature.

Ravi founded the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) 27 years ago with the aim of reducing conflict between humans and nature. Understanding how conflict has arisen is critical in finding effective and appropriate solutions.

Traditionally, to reduce human elephant conflict, elephants would be fenced in to National Parks with the intention of keeping them away from farmer’s crops. Unfortunately, elephants are not cattle and this ‘solution’ did not take into account the specific needs of elephants. It deprives them from accessing land areas that are important to them during their life cycle. Wild elephants follow cyclical movements using elephant corridors, pathways, they create to find food in the forest and water sources.

Finding a sustainable solution necessitates that both the human and elephant needs are respected. Rather than fencing the elephants into an area, Ravi’s response instead focuses on fencing the elephants out of areas that need to be protected from them. Electric fences erected around homes and crops protect communities and their livelihoods.

This has been a successful remedy for over 20 years, and has been replicated in other parts of the world. However, electric fences are not the most appropriate response for every situation. Solving any issue requires creativity, and I love the alternative options developed and implemented by SLWCS.

One alternative solution harnesses the power of nature. Asian elephants don’t like the smell of citrus! Since 2006 Project Orange Elephant has planted 45,000 orange trees around communities which have a history of human elephant conflict. These orange trees provide crops with a natural defense system and have created an environment of co-existence with villagers reporting a significant reduction of their property being attacked by elephants. The oranges provide the additional, and welcome, benefit of generating a secondary, and in some cases, primary income source for farmers.

Environments where elephants and humans co-exist in mutual tolerance can be negatively impacted by an influx of people. Especially if these people have no previous experience of living in an area with wild elephants. Lack of understanding can lead to fear, which can incite action, which can escalate to human elephant conflict, and result in elephants being killed.

Electric fencing, nor orange trees, were an appropriate answer for a situation created as a result of a human population increase in a rural area. Concerned parents were walking their children to school through an elephant corridor, and carrying guns to protect them against elephant attacks. Instead, the remedy crucially required a tactic that reduced opportunities for contact between humans and elephants. With the inauguration of the EleFriendly bus children now travel to school safely, and the elephants continue to use the elephant corridors without being shot.

As a tourism destination, Sri Lanka offers something for everyone; beaches and rainforests, history, culture and festivals. Ravi anticipates that when tourists return there will be an increased appetite for responsible tourism. He has a strong conviction that every one of us should contribute to conservation, and that conservation of species and habitats should be a global activity alongside minimising plastic waste and carbon dioxide emissions.

SLWCS reflect this conviction by offering a range of volunteer programmes, including planting orange trees and e-volunteering. Each programme helps protect local communities, wildlife and habitats. Volunteers working with local farmers reinforce the message that resolution rather than conflict is a better outcome for everyone.

At 15 years old, Ravi felt helpless to save the marshes, but this feeling ignited his determination to protect natural history and nurtured his understanding of the importance of conservation.

Conservation of our natural environment is what assures us of the ongoing protection of our landscapes and wildlife. It is the way to safeguard diversity on earth and is crucial for our own survival.

Despite our conversation being at 3:00am for Ravi, he was fired up and full of enthusiasm as he shared with me the work and impact of SLWCS. There was so much wisdom in what he shared throughout our conversation. ‘You can change humans’ behaviour; you can’t change wildlife’s behaviour.’ This strikes me as a profound statement. Despite filling me with despair, as it seems to be very difficult for many of us to change our behaviour and see beyond our own immediate needs and wants, equally it offers hope, that as a species we have the ability to modify our behaviour to work within the boundaries of the resources available to us. If oranges can mitigate human elephant conflict, then what other solutions does nature offer us to resolve issues?

Learn more about SLWCS and their unique model for sustainable conservation which includes field research, applied conservation, and sustainable economic development: https://www.slwcs.org/our-story

Volunteer programmes offer you the opportunity to help SLWCS both in Sri Lanka and remotely as an e-volunteer. Details are available here: https://www.slwcs.org/volunteer

IRENE MILLAR

Passionate about sustainability, Irene would like to hear stories from people in the travel industry with knowledge, dedication and insight, on how they make a positive difference to their local communities, habitats and environment through applying sustainability principles and practices.